The Competition Authority has concluded its investigation into Samskip's breaches of competition law with Decision No. 33/2023. The Authority has concluded that Samskip has seriously infringed the prohibition in Article 10 of the Competition Act and Article 53(1) of the EEA Agreement, through an illegal agreement with Eimskip.

The conclusion of the Competition Authority is therefore that Samskip, during the investigation of the case, breached Article 19 of the Competition Act by providing incorrect, misleading and insufficient information and failing to hand over documents.

The total administrative fines for the above-mentioned breaches amount to 4.2 billion króna.

Samskip is also required to take specific measures to prevent further infringements and to strengthen competition.

Here you can find a summary and the main events of the case.

The investigation into Eimskip's infringements concluded with the company's settlement with the Competition Authority in the summer of 2021. With the settlement, the company admitted the infringements, paid an administrative fine of 1.5 billion krónur, and undertook certain measures.

The decision concerning Samskip's infringements states:

„The consultation as a whole was intended to enable the companies to significantly reduce competition and to raise or maintain prices for their customers, e.g.d. by increasing prices upon contract renewal, raising tariffs and service fees, introducing new charges, reducing discounts, etc. The combined dominant position of Eimskip and Samskip in the market, the interactions between the companies“ management and other factors in their consultation created ideal conditions for the companies to succeed in their collusion and profit at the expense of their customers and society as a whole."

A summary of the decision is available here:

This decision concludes the investigation into Samskip's infringements of the prohibition on illegal competition. It is the Competition Authority's conclusion that Samskip has seriously infringed the prohibition of Article 10. of the Competition Act and Article 53(1) of the EEA Agreement through unlawful, ongoing collusion between 2008 and 2013 (the main investigation period), with certain infringements having occurred prior to this period. Furthermore, the authority has concluded that during the investigation, Samskip seriously breached Article 19 of the Competition Act by providing incorrect, misleading and insufficient information and failing to produce documents. Samskip hf. and Samskip Holding B.V. are therefore fined a total of 4.2 billion króna for these infringements.

The investigation initially concerned Samskip and Eimskip. The investigation into Eimskip's infringements concluded in June 2021, with a settlement the company reached with the Competition Authority. With the settlement, Eimskip acknowledges „to have engaged in communication and cooperation with Samskip which constituted serious infringements of Article 10 of the Competition Act and Article 53 of the EEA Agreement“ (prohibition of unlawful collusion). With the settlement, Eimskip undertakes certain measures to prevent further infringements and to promote competition. The company also acknowledges „of having infringed Article 19 of the Competition Act by failing to provide necessary or correct information or to submit documents for the purposes of an investigation by the Competition Authority“. Due to the aforementioned breaches, Eimskip paid an administrative fine in the amount of 1,500,000,000 kr., but in determining the amount of the fine, it was taken into account that a company faces lower fines than would otherwise be the case if it comes forward, admits serious breaches and commits to taking measures to prevent further breaches.

When Samskip became aware that Eimskip was in settlement talks with the Competition Authority, the company also requested settlement talks. After talks had taken place in June and July 2021, it became clear that they would not result in an outcome that, in the opinion of the Competition Authority, would constitute a satisfactory resolution of the matter. The talks were therefore terminated.

As the settlement negotiations with Samskip concluded without an agreement, this decision takes a position on whether and how the company has breached competition law. Following the conclusion of the investigation into Eimskip, the Competition Authority has taken Samskip's comments for further consideration and has given the company further opportunities to comment on specific aspects of the investigation.

The Competition Authority's investigation into the conduct of Samskip and Eimskip was prompted by tips it received from, among others, the companies' customers. The tips were considered to provide strong indications that the companies' key executives had extensive contact and that the companies were engaging in illegal collusion, which was manifested, among other things, in their not competing for each other's important customers. The investigation revealed that the allegations were well-founded.

The investigation into the case began with searches at Samskip and Eimskip in the autumn of 2013, on the basis of court orders from the Reykjavík District Court. On the same day and in the following days, several managers of the companies provided the Competition Authority with oral information. Following an initial processing of the data obtained during the raids, the Competition Authority then carried out a second raid at the companies in early summer 2014. Furthermore, further requests for information and data were directed to the companies during the course of the investigation.

The investigation has been a priority for the Competition Authority from the outset. This case is extremely extensive in nature and scope. The investigation thus covered most aspects of the operations of two large international companies that were active in numerous countries. The investigation concerned continuous and multifaceted infringements that had been ongoing for many years. The scale of this investigation is unprecedented in the field of competition law in this country. For example, the copied and seized data amounted to approximately 4 terabytes, which corresponds to tens of millions of documents and emails.

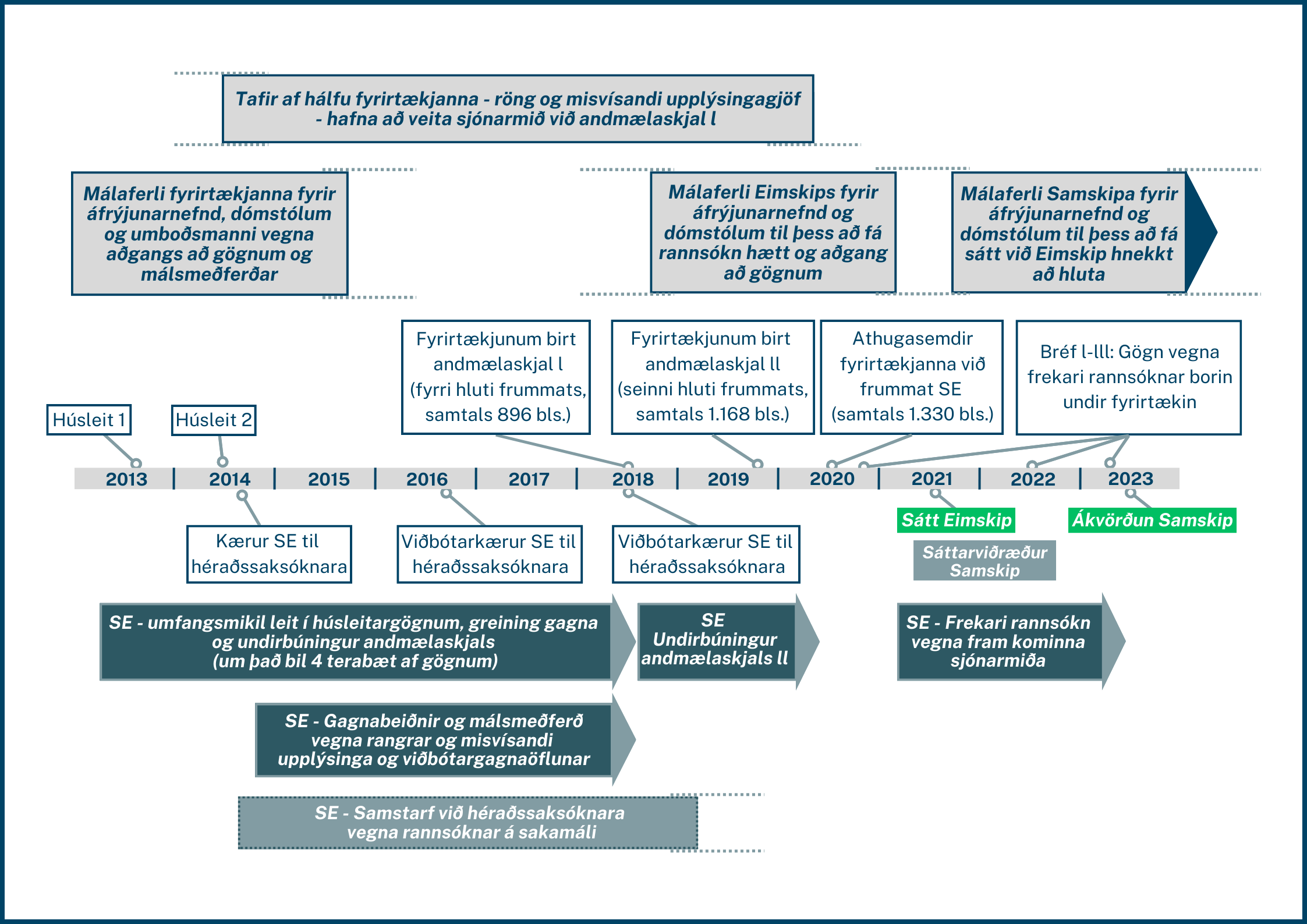

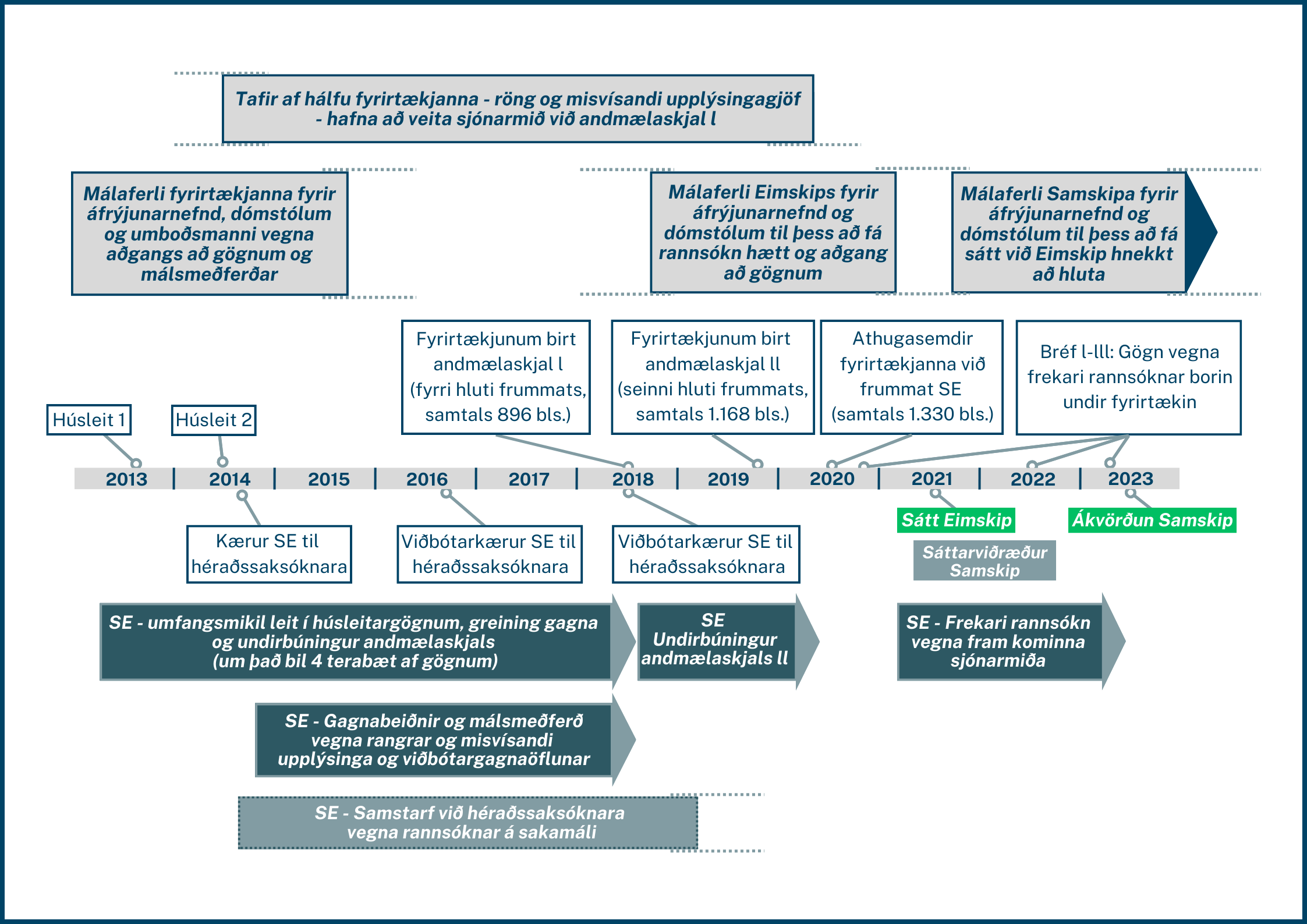

The accompanying diagram provides an overview of the research process, i.e. the main stages of the research and the events that had the greatest impact on its management.

It had a significant impact on the handling of the case that, at the outset of the investigation, both Samskip and Eimskip repeatedly provided incorrect, insufficient or misleading information about the companies' interactions and cooperation. This was first done during oral information provided by management in connection with searches of the companies' premises. Furthermore, the companies failed to provide important information or hand over documents in subsequent requests for information from the authority. This conduct by the companies resulted in significant delays to the investigation. Through its settlement with the Competition Authority, Eimskip acknowledged that it had breached its obligation to provide information under Article 19 of the Competition Act and paid a fine for the administrative offence. This decision concludes that Samskip breached Article 19, and a fine is imposed on the company for this breach. As will be detailed, these infringements by Samskip of Article 19 were extensive, serious and were highly detrimental to the efficient conduct of the investigation.

During its investigation, the Competition Authority issued two letters of objection to the companies, setting out its preliminary findings in detail. The first statement of objections was issued to the parties in mid-2018, and the companies were invited to submit their comments and views. The second statement of objections was issued to the companies at the end of 2019.

The provisions of Article 13 of the Administrative Procedure Act, among other things, grant companies under investigation the right to be heard. This entails that a company can review the case file and comment on its contents before an administrative authority makes a decision. However, the Administrative Procedure Act does not oblige administrative authorities to issue an opportunity to comment. The Competition Authority, however, issues statements of objections in order to promote thorough investigations and to further ensure the right of parties to be heard, in accordance with Article 17 of Regulation No. 880/2005 on the procedure of the Competition Authority. The publication of an objection document is therefore an advantage for the parties to the proceedings, as it ensures „to some extent broader rights than those which are directly derived from section 13 of the Administrative Law Act.“It also appears that the right of a party under the Administrative Procedure Act arises from the publication of a statement of objections and access to information in connection with that publication.„Respected in every respect“, see the judgment of the Supreme Court of Iceland of 27 November 2014 in case no. 112/2014 The Competition Authority v. Langasjó ehf., Síld og Fiski ehf. and Matfugl ehf..

The publication of two letters of objection was intended to give the companies additional scope to present their views and to expedite the handling of the case. However, both companies decided not to do so. Upon the publication of the first objection notice, Samskip decided to withhold their comments and views until the second objection notice was available. Eimskip initially announced its intention to exercise its right of reply in relation to the first submission and requested repeated extensions of time for this purpose, but later changed its mind and decided not to comment until the second submission had been made.

The companies' comments on the Competition Authority's preliminary assessment were not received until 2020. Samskip's final comments on the objections were submitted at the end of August 2020, or more than two years after the first objection was filed and more than eight months after the second was published. Both companies contested the authority's assessment and its finding of infringement of Article 10 of the Competition Act and Article 53 of the EEA Agreement.

Due to further investigation, including in light of the views expressed by Eimskip and Samskip, the companies were written to at the end of November 2020, where they were granted access to further information and given the opportunity to exercise their right of reply.

As previously stated, Eimskip decided to reach a settlement with the Competition Authority regarding the outcome of the case in June 2021. In connection with this, Samskip also requested settlement negotiations, but these did not yield any results. During the further investigation, Samskip was written to on three occasions—in May and July 2022 and March 2023—wherein the company was, amongst other things, granted access to additional evidence and given the opportunity to exercise its right of reply.

Investigation referred to the Court of Appeal, the courts and the Ombudsman of the Althingi

During the investigation of the case, the matter has come before either the Competition Appeals Tribunal or the courts seventeen times. Thus, the companies have submitted seven appeals to the Appeal Board and matters related to the investigation have come before the Reykjavík District Court five times and been brought before the Court of Appeal three times.

The issues before the Appeal Board and the courts can be broadly categorised into three main areas. Firstly, the access of Eimskip and Samskip to search warrants and other documents came before the appellate board and the courts in the first two years of the investigation. Issues concerning the companies' access to the relevant documents were resolved.

Secondly, the investigation came before the courts and the appeals board in 2019 and 2020, primarily at the instigation of Eimskip. Before the appeals board, the company sought to obtain specific documents and information from the Competition Authority. The company also twice requested in the district court that the investigation be discontinued and the case files destroyed. Furthermore, the company argued that certain employees of the Competition Authority were biased from handling the case. The company's claims were dismissed by the district court in the first case, a decision which was upheld by the Court of Appeal. The second case was withdrawn by the company shortly before it requested conciliation talks.

Thirdly, Samskip has sought to have certain provisions of the settlement agreement between Eimskip and the Competition Authority annulled; these provisions relate to the termination of the companies' cooperation. The judgment of the district court in that case has been appealed to the Court of Appeal, where the case is now awaiting a hearing.

In 2015, Eimskip lodged a complaint with the Ombudsman of the Althingi concerning the procedures and practices of the Competition Authority. The Ombudsman took the complaint under consideration and requested information from the Competition Authority. Having received the Competition Authority's responses, the Ombudsman considered that there was no basis to take action regarding the complaint.

Section 2 of this decision contains an overview of the proceedings, and Annex II provides a detailed account of the individual elements of the proceedings in chronological order.

Complaints to the Office of the District Attorney

In accordance with Article 42 of the Competition Act, the Competition Authority shall assess, taking into account the gravity of the infringement and law enforcement considerations, whether the part of the case concerning the criminal liability of an individual should be referred to the police, The Office of the District Prosecutor is responsible for the investigation and prosecution of criminal offences under the Competition Act.

Provision 42 also allows for the mutual exchange of information between the Competition Authority and the police authorities. The Competition Authority is also authorised to participate in police operations concerning the investigation of breaches of competition law, and the police are likewise authorised to participate in the operations of the Competition Authority.

The Competition Authority has, on three occasions during its investigation, referred complaints to the District Prosecutor's Office concerning certain employees of Samskip and Eimskip. This was done in 2014, 2016 and 2018. During its investigation, the Competition Authority has also shared documents and information with the District Public Prosecutor, in accordance with the aforementioned powers, and has assisted the office with interrogations. Furthermore, the district prosecutor has granted the Competition Authority access to documents and witness statements which have been used in the investigation of the case and form part of the case file.

In the regional prosecutor's investigation, two directors from Samskip and two directors from Eimskip were served with witness statements. According to the Competition Authority, the individuals in question still have the status of suspects. Its investigation is ongoing.

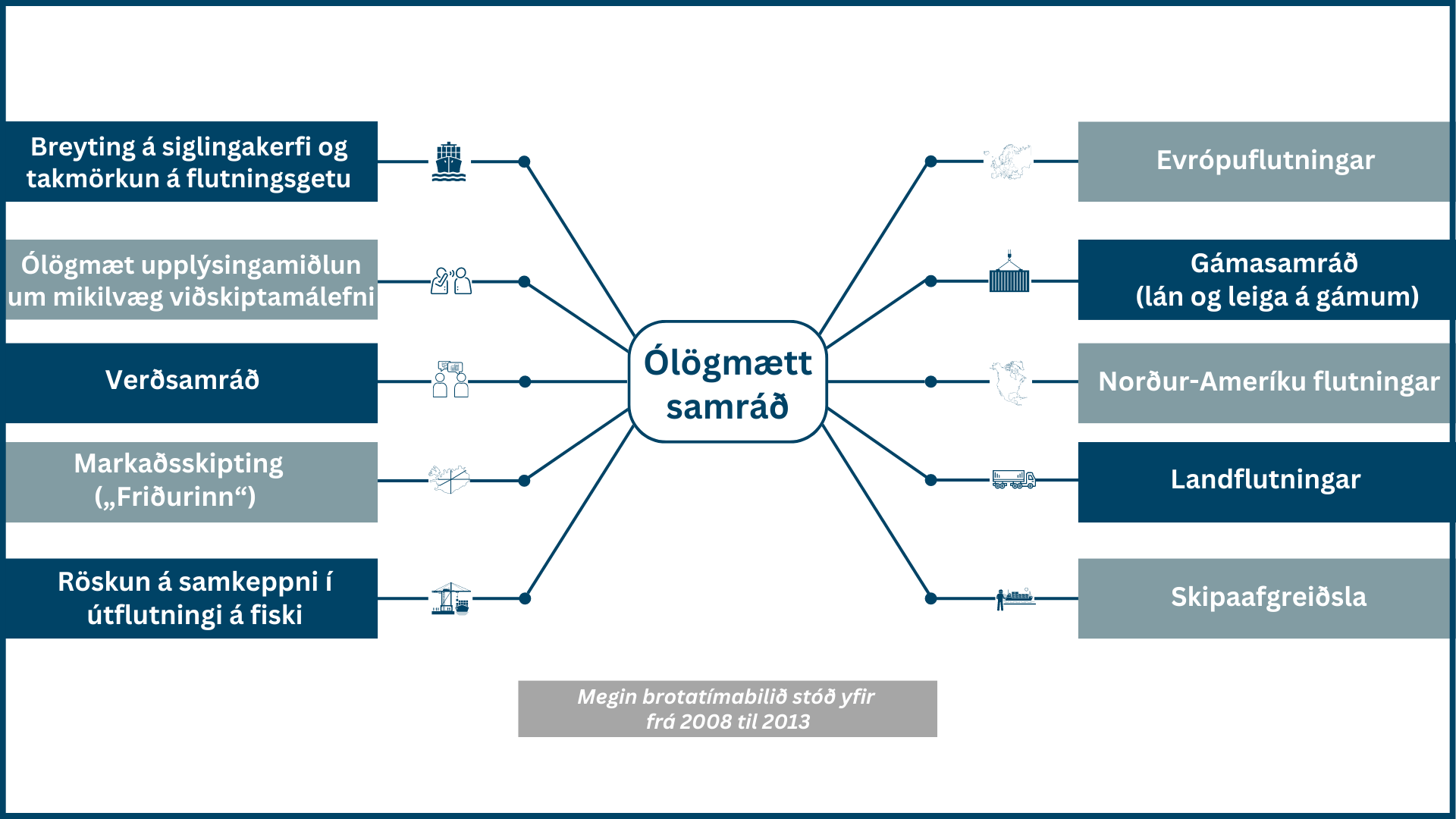

As previously stated, the Competition Authority's conclusion is that Samskip has seriously breached the prohibition in Article 10. Article 10 of the Competition Act and Article 53(1) of the EEA Agreement by means of an unlawful continuous concerted practice between 2008 and 2013, as well as certain infringements having occurred prior to this period. Samskip's infringements include, among other things, the following conduct:

The high-level overview can be summarised in the following overview diagram:

Samskip's infringements were serious and extensive, and spanned a long period, in markets where the participants in the cartel held a dominant position. During the period, Samskip and Eimskip together had a share of over 90% in sea transport between Iceland and Europe, 100% in sea transport between Iceland and North America for the entire period, and a share of over 75-80% in land transport, on a nationwide basis. The companies have been among the largest in Iceland, and their revenues from transport operations amounted to around 2.4-2.6% of gross domestic product (i.e. the value of all goods and services produced and offered each year).

Competition in transport is of great importance for the standard of living of the general public and the competitiveness of Icelandic business life. There were therefore compelling public interests in Eimskip and Samskip respecting the ban on any form of anti-competitive collusion between rivals. Otherwise, consumers, businesses and the national economy as a whole could suffer significant economic damage.

Background to increased consultation

The evidence shows that during the first half of 2008, Samskip hf. in Iceland was considering how to respond to worsening economic prospects and a declining demand for imports. Two options were considered. On the one hand, to increase Samskip's competition with Eimskip, i.e. to win over Eimskip's customers and improve vessel utilisation. On the other hand, to increase Samskip's cooperation with Eimskip. The latter option was chosen.

Although the operations of Samskip hf. in Iceland had been successful, Samskip Holding, the Dutch parent company of the Samskip Group, and its main owner faced financial challenges in 2008. On the one hand, due to the demands of Samskip Holding's main lender, Fortis Bank, and on the other, due to the challenges the main owner faced as the second-largest shareholder in Kaupþing Banki hf. in the run-up to the collapse, through investment companies.

In March 2008, the principal owner of Samskip instructed board members and key executives to take action to protect and enhance Samskip's position in Iceland as „cash cow“ for the Samskip Group („…maximise the business and protect the Cash Cow which Iceland has been for the Group“). Clear instructions were thus given, among others, to the CEO of Samskip in Iceland to ensure and increase cash flow from the company's operations in Iceland to Samskip Holding. The evidence shows that Samskip's main shareholder urged the CEO to exert influence in the negotiations with Eimskip, including by promising a bonus payment.

At the same time, Eimskip was experiencing severe financial difficulties, which were primarily caused by debts from overseas investments. In May 2008, there was a change of CEO at Eimskip. In an email from the CEO of Samskip to Samskip's main owner, his assessment is expressed that with the change there will „Greater softness, and reduces hardness“. The CEO of Samskip said he knew the new CEO of Eimskip well.

These and other contacts between key executives of Samskip and Eimskip undoubtedly made it easier for Samskip than would otherwise have been to approach Eimskip with the aim of increasing the companies' illegal collusion. Furthermore, the communications and relationships were conducive to maintaining the illegal collusion throughout the investigation period of this case.

Decision on increased consultation

The evidence in the case shows that Samskip and Eimskip had engaged in certain illegal collusion since at least 2001, but the most serious offences in this case began in the run-up to the economic collapse in 2008. That 6 June 2008 The principal owner of Samskip, the CEO of Samskip, the chairman of the board of Eimskip and the new CEO of Eimskip met at the premises of Kjalarr, the investment company of Samskip's principal owner. At this meeting, Samskip and Eimskip decided to launch a project which the companies named „A new beginning“This project aimed to distort competition within the meaning of Article 10 of the Competition Act and was unlawful.

The purpose of the project was to examine the benefits for the companies of „to increase“the illegal collusion between the companies that was then in place. The collusion that was already in place in June 2008 was, inter alia, as follows:

In „A new beginning“The project involved Samskip and Eimskip deciding to exchange sensitive information and jointly assess the benefits of increasing cooperation in core aspects of their operations. This included shipping systems, sea transport to and from Iceland, market sharing, vessel handling in Iceland, land transport in Iceland, and subsidiaries in Norway that handled the export of frozen fish from, e.g. Iceland and Norway, freight forwarding, sea transport between ports on the European mainland (so-called „short sea“ transport) and the operation of cold stores in the Netherlands.

During the investigation period, the managers of the companies involved in the consultation held numerous meetings and conversations. For example, between June 2008 and January 2009, the companies' managers held at least 19 meetings to discuss individual aspects of the collaborative project. In addition, contemporaneous evidence shows that the relevant managers communicated by telephone or email on at least 18 occasions during the same period.

The image below describes some events in the early days of the enhanced consultation, up until late July 2008.

Contemporary evidence shows that between 2009 and September 2013, the companies' managers and key personnel had contact on at least 160 occasions, through meetings, telephone calls, at golf tournaments, on trips, at dinner parties or otherwise. Emails between the companies are not included in this figure. Chapter 13 of the decision sets out these interactions, as well as their significance to the case.

Among the key evidence of Samskip's infringement are internal documents from the companies, in particular emails between colleagues, which shed light on the preparation for the consultation within each company. The evidence sheds light on the preparation for and content of meetings and other communications between the companies, as well as the preparation for and conduct of the collusion more generally. For example, the evidence shows in detail how the companies coordinated the preparation and execution of individual aspects of the collusion.

The above-mentioned communications between Samskip and Eimskip during the relevant period comprised repeated discussions between managing directors and heads of department who were, among other things, responsible for shipping networks, land transport networks, pricing of transport services and other competitive aspects of the companies' services. The evidence shows that the companies' discussions concerned core aspects of their transport operations and competition.

Second half of 2008: Foundations for increased cooperation laid

In the latter half of 2008, in consultation with Samskip and Eimskip, all work components falling under „A new beginning“their projects, including capacity constraints and increased cooperation in maritime transport. The worsening economic conditions led to a contraction in imports into the country. It was clear that unused transport capacity was costly for the companies and created an incentive for increased price competition, in order to secure greater volumes of freight. At the same time, Samskip's management planned to increase exports from the country with the same vessels, not least due to an increase in Samskip's transport of aluminium for Alcoa Fjarðarál. The measures involved, among other things, limiting import capacity, whilst at the same time having sufficient capacity to maximise revenue from important exporters such as Alcoa and seafood producers.

An important milestone in the cooperation between Samskip and Eimskip was reached in the summer and autumn of 2008, with changes to sailing schedules and a limitation of capacity. The companies also consulted on various support measures to ensure the overall success of the cooperation. In connection with Samskip's decision at the end of October 2008 to reduce the number of vessels on routes to and from Iceland from four to three, Eimskip, for example, undertook to transport part of the aluminium that Samskip would otherwise have carried for Alcoa. Based on the consultation, Samskip was therefore able, on the one hand, to reduce its service to Alcoa and, on the other, to increase prices by 131% for that important customer. Within Eimskip, there was great satisfaction with these shipments, which the company received on the basis of the collusion, and this was described, among other things, as „bliss“Eimskip also undertook substantial freight transport for Samskip from the UK to Iceland. At the same time, the companies' key executives were engaged in repeated illegal communications. Concurrently, both companies worked on significant price increases and had communications with each other relating to their pricing decisions.

Official and other data show that the severe economic difficulties which swept the world in the autumn of 2008 had the effect, both in this country and in neighbouring states, of significantly reducing the demand for the services of transport companies and that important purchasers of such services req...better terms as their operations came under pressure. This situation led to intense price competition in foreign transport markets and, for example, a report in Morgunblaðið on 30 October 2008 stated that „freight charges have never fallen so much.

Due to the collusion between Samskip and Eimskip here in the country, the companies were able, on the other hand, to repeatedly raise prices in the latter half of 2008. As a sign of this, the CEO of Samskip stated in October 2008 that the company had achieved „massive increases“. The reaction of a Eimskip customer to the company's price increase in November 2008 was: „Are you mad? Who agrees to an 80% increase?“Contemporaneous evidence confirms numerous complaints from the companies' customers protesting against price increases, citing, among other things, a significant drop in oil prices and an unprecedented fall in prices on foreign transport markets. As a result of the collusion, Samskip and Eimskip, on the other hand, did not have to fear competition from each other and were able to ignore complaints and protests.

This part of the case is discussed in detail in chapters 8–11 of this decision.

„Peace“: 2009 – 2012

Accordingly, during the latter half of 2008, Samskip and Eimskip had taken significant measures to ensure that their consultation would be successful in the circumstances prevailing in Icelandic business life.

At that time, a relatively small group of larger customers was of paramount importance to the operations of both Samskip and Eimskip. For instance, at a certain point in time, 38 out of a total of 1,800 customers accounted for 661 TP3T of Samskip's revenue from transport to the country. In such circumstances, there is an obvious risk that collusion between competitors to reduce capacity will not, by itself, be sufficient to raise prices or defend against price reductions. Thus, a key customer of one company could solicit business from the other, which might then conclude it would be more profitable to win that business than to honour the collusion.

Samskip and Eimskip prevented this danger by means of an unlawful market division. In accordance with this, Eimskip has admitted that after 6 June 2008 it engaged in consultation „with Samskip on the division of markets by major customers in sea and land transport.This meant that the companies would not try to take such customers from each other through competition.

Eimskip's aforementioned admission is fully consistent with contemporary data, as for the vast majority of the period, important customers did not switch between Samskip and Eimskip. It made no difference, even though the customers repeatedly sought quotes for the business, put it out to tender or otherwise tried to obtain better terms and to fend off price increases from Samskip and Eimskip.

The consultation between Samskip and Eimskip as a whole was such as to enable the undertakings to restrict competition effectively and to raise or maintain prices vis-à-vis their customers, e.g.d. by increasing prices upon contract renewal, raising tariffs and service fees, introducing new charges, reducing discounts, etc. The joint dominant market position of Eimskip and Samskip, the interactions between the companies' management and other factors in their collusion created the ideal conditions for the companies to succeed in their collusion and profit at the expense of their customers and society as a whole.

An example of the above is Ölgerðin's tender in 2009, as the company was one of Eimskip's most important customers. At the beginning of 2009, Ölgerðin was extremely dissatisfied with the significant price increases for Eimskip's sea freight service, which were also inconsistent with the companies„ agreement. Ölgerðin also considered the price of Eimskip's land transport service to be 'absurd“. Within Eimskip, however, no action was taken on Ölgerðin's complaints, as Eimskip had nothing to fear from competition for the business due to its collusion with Samskip. Instead, Eimskip's management passed Ölgerðin's complaints between themselves to „entertainment“.

Subsequently, Ölgerðin decided to tender out all its transport business. Just before the opening of tenders at Ölgerðin, five of Samskip's senior executives held a meeting.„competition“...between the executives as to who had guessed the correct Eimskip bid price in the tender. All the executives' predictions, however, were based on Eimskip bidding a lower price than Samskip in all parts of the tender. The tension/competition among the Samskip executives was therefore which of them had correctly guessed Eimskip's bid price, not whether Samskip would secure the contract with Ölgerðin.

The data therefore shows that Samskip's offer to Ölgerðin was a sham offer. The collusion between Samskip and Eimskip resulted in Eimskip retaining the business and managing to increase the price for this customer. At a meeting at Eimskip, there was great satisfaction with the outcome, and a company director stressed this to his subordinates: „He drew the line at us lowering the prices. We need to raise them rather than lower them […]. Shipments could be larger these days.“.

The situation resulting from the consultation is described in the companies„ contemporary records as 'peace“ (or „calm“ in the market). Instead of active competition for important customers, „peace“and a mutual certainty about the competitor's response. On that basis, the companies focused on maintaining or raising the price.

One manifestation of this was that in their annual plans, both Samskip and Eimskip assumed they would be able to repeatedly raise prices and, at the same time, retain their most important customers.

At the beginning of the period under review, there were significant economic difficulties abroad, as well as challenges in the company's international transport operations. Samskip Holding operated transport services in various other European countries, as well as in Iceland. The company's board minutes state that there was a significant decline in demand in foreign shipping markets. Contemporary data show that the company's clients pressed for price reductions in the foreign shipping markets in which the group operated. Furthermore, it is clear that the economic difficulties had the effect of reducing key cost factors, such as oil and vessel charter rates, which in turn made price reductions possible. Minutes from Samskip Holding's meetings state that this led to intense and even desperate competition in the international shipping markets. This had a significant impact on the performance of the company's subsidiaries. The same Samskip Holding minutes describe a completely different situation for Samskip hf. in Iceland.

In these minutes of Samskip Holding, a great deal of satisfaction with the performance of Samskip hf. in Iceland is thus expressed. Examples of this are:

In this regard, it should be noted that although Samskip's turnover in Iceland in 2009 was only about a quarter of the group's total turnover, the operations in Iceland generated around 80% of the group's EBITDA. This demonstrates the success of Samskip hf. in Iceland as a„Cash Cow“ for the group, as the principal owner had laid out and instructed in the run-up to the increased co-operation in 2008.

An example of this is an email sent by the Managing Director of the International Division at Samskip to, among others, the CEO of Samskip on 15 December 2010. These key executives were then in Rotterdam to present to the board of Samskip Holding the results for the first ten months of 2010 and the plan for Samskip hf. in Iceland for 2011. The email said only this:

„The cash cow has arrived“

Attached to the Director's email was a picture of a dairy cow, and it was clear that this was a reference to Samskip hf. in Iceland. This is discussed in more detail in the decision, section 14.33.15, paragraphs 7236-7237.

2013: Reduces the scope of the consultation

In 2013, Samskip reduced its cooperation with Eimskip. At this time, the economic recovery in Iceland created an incentive for the companies to increase the volume of freight in their shipping networks and to move away from the cooperation they had initiated following the economic crash of 2008. At the same time, Alcoa also ceased its export business with Samskip and Eimskip, which resulted in a significant volume of freight leaving the companies' shipping networks, particularly Samskip's.

In accordance with Article 21 of the Competition Act, the Competition Authority shall apply Article 53 of the EEA Agreement in Iceland. Article 53 of the EEA Agreement prohibits restrictive business practices by undertakings and their associations that may affect trade between the EEA States.

The assessment of whether an infringement has such an effect is based on the EFTA Surveillance Authority's guidelines and case-law. It is the conclusion of the Competition Authority that the infringements in question in this case were liable to affect trade between EEA States within the meaning of Article 53 of the Agreement.

The substantive provisions of Article 53 of the EEA Agreement are fully comparable to the provisions of Articles 10 and 12 of the Competition Act, as the Competition Act in this respect is modelled on EEA/EU competition law. In this decision, detailed arguments are presented that Samskip has seriously infringed Article 10 of the Competition Act. By reference to the same reasoning, the Competition Authority concludes that Samskip has infringed Article 53 of the EEA Agreement. It follows that the Competition Authority's assessment of whether Samskip's conduct breached Article 10 of the Competition Act also applies to Article 53 of the EEA Agreement.

The Competition Authority has concluded that Samskip, during the investigation of this case, was guilty of providing incorrect, misleading and insufficient information and failing to provide documents. By doing so, the company breached Article 19 of the Competition Act, which provides for the Competition Authority's powers to obtain evidence during the investigation of individual cases. This concerns administrative fines for breaching the obligation to provide information and submit documents, pursuant to Article 37(1)(i) of the Competition Act. In the settlement between Eimskip and the Competition Authority, the company admits an infringement of Article 19 and pays a fine for this.

Samskip's breaches consisted of providing false, unsatisfactory or misleading information during oral debriefings in connection with the Competition Authority's searches at the company on the 10th. and 17 September 2013, the company repeatedly provided false, insufficient or misleading information about its communications and cooperation with Eimskip. Samskip's infringements also consisted of failing to provide information or to hand over documents in accordance with requests made to the company during the investigation.

These breaches were extensive and serious. They hindered and delayed the investigation of the case, as the Competition Authority was misled and significant information was withheld from the investigation from its very early stages.

A breach of Article 19 is dealt with in Chapter 23 of the decision.

In accordance with Article 37 of the Competition Act, the Competition Authority imposes administrative fines on undertakings or associations of undertakings that breach, among other things, the prohibition on illegal collusion under Article 10 of the Competition Act or Article 53 of the EEA Agreement. The same applies to breaches of the obligation to provide information and submit documents under Article 19 of the Competition Act.

Decisions by competition authorities concerning infringements of competition law and the fines imposed for them are intended, among other things, to create a deterrent effect, to deter companies from continuing or repeating their infringements, and at the same time to create the conditions for more effective competition, which in the short or long term benefits the public.

The Competition Authority's investigation has concluded that Samskip hf., Jónar and Samskip Holding are one and the same undertaking (a single economic unit) for the purposes of competition law. In accordance with this, the Competition Authority has exercised its power to issue a fine against the parent company, Samskip Holding, in addition to Samskip hf. This measure is best suited to ensure a sufficient deterrent effect.

When determining the penalties, the Competition Authority takes into account, among other things, the nature and extent of Samskip's infringements, how long they lasted, the size and turnover of the company, the combined market share of the undertakings in the market or markets concerned, the size and importance of the market concerned, the role of the undertaking in initiating the infringements and whether the infringements were carried out.

Article 37 of the Competition Act provides for a specified maximum fine, i.e. up to 10% of the total turnover of the previous calendar year of the undertaking concerned in the restriction of competition, but the same limit applies in EEA/EU law. Samskip Holding's total turnover in 2022 was 137 million króna.

The above is discussed in detail in sections 35.1 and 35.2 of the decision. With reference to that discussion, the Competition Authority has concluded that an appropriate fine for Samskip's breaches of Article 10 of the Competition Act and Article 53(1) of the EEA Agreement is four billion króna.

In assessing Samskip's breaches of Article 19 of the Competition Act, the Competition Authority takes into account, among other things, that the effective enforcement of competition law depends in no small part on companies under investigation complying with instructions to provide information and hand over documents. In this case, it is established that Samskip's breaches of the obligation to provide information under Article 19 of the Act are extensive and serious. They worked strongly against the effective investigation of the case and delayed it.

In light of this, the Competition Authority has determined that an appropriate fine for breaches of Article 19 of the Competition Act is two hundred million króna. This is discussed in more detail in Chapter 35.3.

By this decision, pursuant to the dispositive wording in 35.5, it is concluded, as previously stated, that Samskip has, by its conduct, breached the prohibition on unlawful cooperation in Article 10 of the Competition Act and Article 53 of the EEA Agreement. Furthermore, it is concluded that the company has breached Article 19 of the Competition Act by providing incorrect, misleading and insufficient information and by failing to submit documents. The decision provides that Samskip Holding B.V. and Samskip hf. shall jointly and severally pay an administrative fine totalling 4.2 billion króna. The administrative fines shall be paid into the state treasury within one month of this decision.

The decision then gives the following instructions to Samskip.

i. Samskip reviews all contracts with other transport service providers to ensure they comply with competition law.

ii. All commercial cooperation with Eimskip and its affiliated companies must cease, if any exists. This also means that Samskip must not cooperate with other companies in any type of transport service if Eimskip also cooperates with that company. This does not apply if Samskip can demonstrate to the Competition Authority that the relevant cooperation is of such a nature that there is no risk of distorting competition between Eimskip and Samskip.

iii. Ensure that all managers and employees are informed of the requirements that competition law places on the company's operations. To this end, there shall be a competition law programme, procedures to ensure its implementation, and organised and regular training.

Breach of the instructions is subject to sanctions under Chapter IX of the Competition Act.

The investigation into the offences of Samskip and Eimskip has been very extensive. It has involved powerful international companies, concerned important markets, and spanned a long period. This is the most extensive investigation by the competition authorities ever conducted in this country.

From the foregoing, it follows that the decision in this case is very extensive. It is presented in 15 volumes and is organised as follows:

In describing the illegal collusion, it is of fundamental importance to explain how decisions were made and how it was carried out. It is therefore unavoidable to describe the involvement of employees who played a key role within the companies. This applies to employees of both companies, even though this decision concerns Samskip. Furthermore, it is unavoidable to describe certain interactions between the companies and their clients, particularly company directors, which are relevant to the case.

In the version of this decision published to the parties to the case, managers and employees in key positions within Samskip and Eimskip are identified by an abbreviation of their name. In the version published publicly by the Competition Authority, the name abbreviations have been removed, and instead managers and staff in key positions are identified by abbreviations that generally indicate their position and role within the company. In this regard, it should be borne in mind that during the investigation period, staff to some extent changed roles or left their employment, and the job descriptions of individual employees also changed. In such cases, the identification covers the employee's duties that best describe the role they played in the matter.

In the decision, Samskip employees are identified in red and Eimskip employees in blue.

All underlinings in this decision are made by the Competition Authority unless otherwise stated.

A data protection impact assessment has been carried out upon the publication of the decision.

The perspective of Samskip and coverage of it

Samskip deny having engaged in unlawful collusion with Eimskip. Samskip also deny having breached Article 19 of the Competition Act in relation to the provision of information and the exchange of documents in the case. Samskip make various submissions in support of this. In Chapters 2–23 Where relevant, reference is made in the relevant discussion to Samskip's comments and they are, where appropriate, briefly addressed. However, as a general principle, Samskip's comments are addressed and a position is taken on them in Chapters 24 – 34. The procedure is such that the relevant sub-chapters in Chapters 2-23 refer to Samskip's comments on the matter, and then refer to where in Chapters 24-34 the main discussion of the relevant Samskip comments can be found. An example of the above is chapter 8.7. In that chapter, the Competition Authority concludes, after assessing contemporaneous evidence and comments from Samskip, that a meeting between the managing directors of land transport for Samskip and Eimskip at the Mokka café on 4 July 2008 was part of the illegal collusion. Samskip's comments are then referred to as follows:

„Samskip maintain that the aforementioned communications (E)frkvstj-innanl and (S)frkvstj-innanl of 4 July 2008 were lawful and entirely unrelated to the „imaginary“ „New Beginning“ project. As is argued in section 25.18, the Competition Authority cannot agree with the company's views.“

The Competition Authority has Issued opinion no. 1/2023 calling for measures to be taken to reduce barriers to competition in the transport market, create transparency and thereby strengthen competition.

At the bottom of the page, the decision, together with its appendices, is available in bound volumes. Below are answers to any further questions that may arise.

Decision No. 33/2023 concerns Samskip's infringements of competition law. The investigation initially concerned Eimskip and Samskip, but the investigation into Eimskip's infringements concluded in June 2021, with a settlement the company reached with the Competition Authority.

With the settlement, Eimskip acknowledges „to have engaged in communication and cooperation with Samskip which constituted serious infringements of Article 10 of the Competition Act and Article 53 of the EEA Agreement“ (prohibition of unlawful collusion). With the settlement, Eimskip committed to certain measures in order to prevent further breaches and to promote competition. The company also acknowledges „of having infringed Article 19 of the Competition Act by failing to provide necessary or correct information or to submit documents for the purposes of an investigation by the Competition Authority“.

Due to the aforementioned breaches, Eimskip paid an administrative fine in the amount of 1,500,000,000 kr., However, in determining the amount of the fine, it was taken into account that a company faces lower fines than would otherwise be the case if it comes forward, admits serious breaches and commits to taking measures to prevent further breaches.

The notice regarding the settlement, dated 16 June 2021, together with the settlement itself, is available. here.

As Samskip's infringements concern the company's collusion with Eimskip, decision no. 33/2023 also constitutes infringements by Eimskip.

This decision is momentous. The investigation into the infringements by Samskip and Eimskip has been very extensive, involving powerful international companies, affecting important markets and spanning a long period. This is the most extensive investigation conducted by competition authorities in this country. The decision reflects this.

Intervention by competition authorities is an onerous remedy for the undertakings concerned and requires the publication of the decision, but such publication serves a multi-faceted purpose, including the following:

The investigation has been a priority for the Competition Authority from the outset. There was no undue delay or inaction in the Authority's handling of the case and investigation. This was a very extensive investigation, covering most aspects of the operations of two large international companies that were active in numerous countries. The investigation concerned continuous and multifaceted breaches that had been ongoing for many years. The scale of the investigation is unprecedented in the field of competition law in this country. For example, the copied and seized data amounted to around four terabytes, equivalent to tens of millions of documents and emails.

The following events and matters had a significant impact on the handling of the case:

1) It had a significant impact on the handling of the case that, at the outset of the investigation, both Samskip and Eimskip repeatedly provided incorrect, insufficient or misleading information about the companies' interactions and cooperation. This was first done during oral debriefings in connection with searches at the companies' premises. Furthermore, the companies failed to provide information or hand over documents in subsequent requests for information from the regulator. This conduct by the companies resulted in significant delays to the investigation.

As previously stated, Eimskip has admitted to having breached the transparency obligation of Article 19 of the Competition Act by this conduct and has paid a fine for it. This decision concludes that Samskip has also breached the Competition Act in this respect and imposes a fine.

2) The investigation was also delayed by the companies' decision not to respond immediately to the letters of objection issued by the Competition Authority. An objection notice informs a party to the proceedings of the basis of the case and the authority's preliminary assessment, and gives the party an opportunity to present their views and explanations.

To expedite the handling of the case, the supervisory authority sent a letter of observations in two stages. The companies, however, chose not to comment on the first letter of observations, but to await the second. Samskip's final comments on the objections were not submitted until more than two years after the first objection was served and more than eight months after the second was published. This delayed the investigation.

3) During the investigation of the case, the matter came before the Competition Appeals Board and the courts seventeen times. Thus, the companies lodged seven appeals with the Appeal Board and matters related to the investigation came before the Reykjavík District Court five times, and on three occasions cases were brought before the Court of Appeal. Issues have been addressed such as access to search warrants and data, a demand to halt the investigation, the alleged incompetence of staff, and Samskip's demand that certain provisions of the settlement with Eimskip be declared null and void. Furthermore, the handling of the case led to an investigation by the Ombudsman of the Althingi following a complaint from Eimskip.

Furthermore, it is worth noting that it is well established in competition law that the investigation of extensive and, where applicable, complex infringement cases can be time-consuming. Recent cases include the judgment of the EFTA Court of 5 May 2022, Telenor v. EFTA Surveillance Authority. In this case, the ESA's investigation into Telenor's abuse of a dominant position began in 2012. In 2020, the ESA made a decision and imposed a fine on Telenor for infringements of Article 54 of the EEA Agreement. Telenor requested that the fine be reduced because the proceedings had taken too long. The court did not agree. The court's press release explained this conclusion as follows: „As regards the length of the proceedings, the EFTA Court found that there had been no undue delay or any inaction in connection with the proceedings before the ESA. Although ESA's detailed investigation had inevitably led to the proceedings becoming longer, the EFTA Court considered that the duration was reasonable in view of the case's complexity and scope, and necessary to ensure Telenor's right of audience.“

Also, by way of example, on 21 August 2023 introduced by US competition authorities agreement two parallel pharmaceutical companies, regarding an investigation into illegal collusion that began in 2014. The Competition and Markets Authority then published its preliminary assessment in Objection documenton 24 May 2023, concerning an investigation into the collusion of five banks, which began in 2013.

The nature of the case also means that the operational discretion of the competition authorities can generally affect the outcome of proceedings.

Further information on the handling of the case and the breach of the obligation to provide information and submit documents to the Competition Authority can be found in the summary of the decision and in chapters 2, 23 and 24.2. Furthermore, Annex II provides a detailed account of the proceedings and the Competition Authority's investigation.

The accompanying diagram provides an overview of the research process, i.e. the main stages of the research and the events that most significantly influenced its conduct.

If companies or individuals believe they have suffered damage as a result of a breach of competition law, they can bring a claim against the relevant company, for example by initiating civil proceedings in the courts, see for example the judgments of the Supreme Court of Iceland in cases no. 142/2007, 143/2007 and 309/2007.

In its decisions on breaches of competition law, the Competition Authority does not assess the right to compensation or the damages of individual parties. However, companies or individuals wishing to explore their right to compensation can rely on the Competition Authority's decision and the assessment of the relevant conduct contained therein. They can also request a copy of the relevant case files from the Competition Authority.

In this regard, it is worth mentioning that Directive 2014/104/EU established rules on damages for breaches of EU competition law (Directive 2014/104/EU on Antitrust Damages Actions) The Directive aims to make it easier for companies and consumers to claim damages from companies that breach competition law. Among other things, the Directive facilitates the collection of evidence and the proof of infringements. However, the Directive has not yet been incorporated into the EEA Agreement, and Icelandic law has not been amended to ensure that consumers and businesses here enjoy the legal protection provided by the Directive.

Administrative fines for breaches of competition law shall be paid into the state treasury. If administrative fines are not paid within one month of the decision of the Competition Authority, interest shall be payable on the amount of the fine, in accordance with the 2nd paragraph of Article 37 of the Competition Act No. 44/2005.

Consequently, administrative fines are not used to fund competition enforcement.

In accordance with Article 37 of the Competition Act, the Competition Authority imposes administrative fines on undertakings for breaches of competition law and the competition rules of the EEA Agreement. The Competition Authority is therefore legally obliged to impose such sanctions for serious infringements of competition law. The legislature has determined that fines for competition law infringements may amount to up to 10% of the turnover of the relevant undertaking. The purpose of fines is to create a so-called deterrent effect, thereby preventing the infringing company from re-offending and also serving to make other companies aware of the consequences of, for example, colluding with their competitors. This strengthens competition.

The application of administrative fines in competition matters in this country is based on the policy set out in European competition law, but in EU law, measures have recently been taken to ensure that all states in the region impose such fines and to promote their adequate deterrent effect.

It is sometimes argued that government fines on companies merely lead to the company in question raising the price of its goods or services to finance the fine payments. In this way, the fines ultimately fall on customers and, arguably, consumers.

This argument against government fines does not hold up. Thus, intervention by competition authorities, as the case may be, entails putting a stop to the infringement, and the possibility of the company concerned raising prices on the basis of its infringing conduct (e.g. collusion or abuse of a dominant position) is generally eliminated. Competition from other market players also limits the infringing company's room for price increases.

Furthermore, intervention of this kind is also likely to strengthen competition in the long term, for the benefit of customers and the general public. The deterrent effect of government fines contributes to the above, but it is important that companies are aware that engaging in illegal collusion is costly and risky.

The publication of detailed information about the nature and extent of breaches, as is done in this case, also works against administrative fines being levied on the pockets of customers or consumers.

The Competition Authority therefore intends, in this case, to issue specific recommendations to the customers of the transport companies, urging them to request clarification in each instance on the amount of individual charges levied when entering into a contract. Such follow-up is likely to create a deterrent effect on the companies, in light of the incidents described in the decision.

Furthermore, specific recommendations are made to the government and public authorities to take action to reduce barriers to competition in the transport market and thereby strengthen competition.

The participation of company employees and directors in illegal collusion can result in fines or imprisonment for up to six years, pursuant to Article 41a of the Competition Act. The investigation of such cases is handled by the District Attorney's Office, following a complaint from the Competition Authority. Such a complaint is a prerequisite for an investigation, in accordance with Article 42, paragraph 1 of the Competition Act.

In accordance with Article 42 of the Competition Act, the Competition Authority shall assess, taking into account the gravity of the infringement and law enforcement considerations, whether the part of the case concerning the criminal liability of an individual should be referred to the police.

Provision 42 also allows for the mutual exchange of information between the Competition Authority and the police authorities. The Competition Authority is also authorised to participate in police operations concerning the investigation of breaches of competition law, and the police are likewise authorised to participate in the operations of the Competition Authority.

The Competition Authority has, on three occasions during its investigation, referred complaints to the District Prosecutor's Office concerning certain employees of Samskip and Eimskip. This was done in 2014, 2016 and 2018. During its investigation, the Competition Authority has also shared documents and information with the District Public Prosecutor, in accordance with the aforementioned powers, and has assisted the office with interrogations. Furthermore, the district prosecutor has granted the Competition Authority access to documents and witness statements which have been used in the investigation of the case and form part of its evidence.

During the district prosecutor's investigation, two executives from Samskip and two from Eimskip were served with a letter of formal notification. According to the Competition Authority, these individuals still have the status of suspects. The district prosecutor's investigation is ongoing.

Further information on the liability of individuals under competition law can be found here.

The rules of evidence in cartel cases are derived from legislation and case law. This case also addresses breaches of the prohibition in Article 53 of the EEA Agreement against unlawful cartelisation. In such cases, the competition authorities are bound by the EEA competition rules as they have been developed in case-law, including with regard to the burden of proof in cartel cases.

Section 4.7 of the decision deals in detail with proof in consultation cases. It covers, among other things, the assessment and presentation of evidence, the burden of proof, evidential requirements and various evidential considerations, such as:

On the Competition Authority's website, there is Instructions page for business associations and competition rules. These include, for example, examples of communication and cooperation that may contravene the prohibition on illegal collusion and anti-competitive activity by business associations. These examples also apply to companies, their directors and employees. Thus, companies operating in the same or a related field should, among other things, avoid communications regarding the following:

Decision No. 33/2023 sets out the multifaceted and extensive communications between the relevant undertakings, namely the management and key personnel of Samskip and Eimskip. There was a great deal of communication. At the outset and during the implementation of the enhanced consultation („A new beginning“), between June 2008 and January 2009, the companies' directors had contact on almost 40 occasions through meetings, telephone calls or emails. Contemporaneous evidence shows that the companies' managers and key personnel had contact on at least 160 occasions during the main investigation period, through meetings, telephone calls, golf tournaments, business trips, dinner parties or otherwise. Emails between the companies are not included here.

For example, between 2009 and 2013, Eimskip and Samskip held annual joint golf tournaments, despite the fact that the managing director of Eimskip's legal department had strongly advised the company's management against it.

Communications of this kind can be highly significant in proving an infringement, depending on the circumstances of each case. Thus, evidence that merely shows communications between competitors, but not their content, can be of great value. This could, for example, include data showing that competitors' managers met or spoke on the telephone. Any type of evidence that suggests contact between competitors is considered, such as diary entries, meeting invitations or restaurant bills.

The EU courts have emphasised that infringements of this kind are usually carried out in secret, as the prohibition on and sanctions for collusion are well known. For the same reason, evidence confirming collusion is scarce and fragmentary, if it exists at all. For this reason, in most cases, a conclusion about the existence of an infringement must be based on various coincidences and indicia which, when considered together, can constitute proof of an infringement if there is no other plausible explanation for these matters. Evidence confirming that competitors have discussed matters with each other is considered to be significant indicia in this regard.

The relationships and communications between the managers of competitors can also, in and of themselves, affect whether the companies succeed in maintaining and achieving success in an illegal agreement. Evidence demonstrating communications, including between managers, can therefore be of great significance. The same applies to whether and what information and data have been provided or disclosed in a case concerning the companies' interactions, including between their management.

Further information on communication and the assessment of communication can be found, inter alia, in the following chapters of Decision No. 33/2023:

It is undisputed that anti-competitive cooperation between companies can cause significant harm to consumers, business, and society as a whole. However, competition law recognises that in certain circumstances, cooperation between undertakings can contribute to, amongst other things, increased economic efficiency and technological progress. Therefore, Article 15 of the Competition Act provides for exemptions from the prohibition on illegal collusion, subject to the fulfilment of certain conditions.

Thus, cooperation is required;

· contribute to the improvement of the production or distribution of a product or service, or promote technical and economic progress,

· provide consumers with a fair share of the benefits arising from them,

· do not impose on the relevant companies restrictions that are not necessary to achieve the set objectives,

· does not enable the undertakings to prevent competition with regard to a substantial part of the relevant production or services.

It is the responsibility of the companies concerned to assess whether the above-mentioned conditions apply and to demonstrate this to the competition authorities should an investigation be launched. The Competition Authority has issued guidelines on the application of Article 15 of the Competition Act, which are, among other places, available on a dedicated information page the authority's guidance on this matter.

During the relevant period of this case, the previous provisions of the Competition Act were in force, which allowed companies to apply for an exemption from the Competition Authority on the same substantive grounds as set out above. It was entirely prohibited to commence co-operation without a formal exemption in place. However, the companies did not do so except to a limited extent, as set out in the decision. In certain instances, it is established that an exemption was granted on the basis of incorrect information. Further discussion of this can be found, inter alia, in Chapter 23 of the decision.

In recent years, there has been a growing emphasis on leniency policies in international competition law. These policies allow companies involved in illegal collusion to come forward and inform competition authorities about the conduct. They are therefore an important tool in rooting out illegal collusion between companies. Fines imposed on companies for serious breaches of competition law can amount to up to 10% of their annual turnover.

By reporting a breach and cooperating with the competition authorities, companies can avoid fines or have their fines reduced significantly. The company that is the first to provide the competition authorities with evidence that can lead to an investigation into alleged illegal collusion can expect to have fines cancelled, provided certain conditions are met.

Companies that provide the Competition Authority with evidence that is a significant addition to the evidence the authority already has can expect a reduction in fines.

It is considered that the public interest in rooting out illegal corporate collusion outweighs the fines that are waived when companies cooperate with competition authorities.

Read more about current rules of the Competition Authority.

The participation of company employees and directors in illegal collusion can result in fines or imprisonment for up to six years, pursuant to Article 41a of the Competition Act. The investigation of such cases is handled by the District Attorney's Office, following a complaint from the Competition Authority. Such a complaint is a prerequisite for an investigation, in accordance with Article 42, paragraph 1 of the Competition Act.

According to paragraph 3 of Article 42 of the Competition Act, the Competition Authority may decide not to prosecute an individual. „that he, or a company he works for or is a director of, has taken the initiative to provide the Competition Authority with information or documents concerning an infringement of Article 10 or 12. Article which may lead to the investigation or proof of an infringement, or which are a significant addition, in the opinion of the Authority, to the evidence it already has in its possession.“

This means that individuals can avoid criminal liability by informing the Competition Authority of an offence or by assisting the authority in an investigation that has already begun. The same reasoning underpins this provision as the current rules on the reduction and remission of fines for corporate infringements (the leniency rules).

"*" indicates required fields